From "The Photographic Object, 1970" Oakland: University of California Press, 2016, p. 134-140.

MS: Thank you for agreeing to talk with me about Photography into Sculpture.

CC: I should tell you that by the time I was in the exhibition I had already moved into making audio/visual sculpture projects and installations. I was probably not as dedicated to photography as other people that you’ve interviewed.

MS: There’s a range of how connected people were to photography and whether they went on to make photographs or other kinds of objects.

CC: Yes, looking back at the 1960s, there was already a worldwide interest in photography. Academically speaking, photography was beginning to be accepted as art department curriculum. My experience, like some of my fellow artists during that time, was that I migrated to Bob Heinecken’s class at UCLA as he established the photo department in the fine art school. It was between 1966 and 1970 that I started to make the pieces that ended up in the MoMA show.

I was thinking back to the panel discussion. Ellen Brooks was correct in saying that none of us actually looked back to reflect on what we were doing. It was the beginning of my so-called art career. I didn’t look at photography as a career but as a valuable art tool.

MS: What were some of your early influences?

CC: I went through industrial design as an undergraduate when UCLA had more of a Bauhaus approach to art, where everybody took basic courses together. The Bauhaus idea of integrating art with industry and society really appealed to me. I had a strong interest in technology. I was raised in the San Fernando Valley, and that was where Lockheed was. During World War II, as kids, we were around all those people who were grinding out airplanes by the minute for the war effort. That technology and the film industry made L.A. blossom. Not that I understood that then, but we were exposed to it as kids. Just like if you grew up in Detroit, you’d be more aware of automobiles than other people. Technology was all very new, and I grew up with that. I wasn’t a car freak or anything. It was just that technology itself was interesting. Photography as an art medium was exciting to me because it involved chemistry, light-sensitive materials, and optics.

When I first enrolled at UCLA in 1959, I started out in painting. Then I saw the industrial design department, where they were using industrial tools and all kinds of new materials and immediately changed my major to industrial design. At the time, there was a strong academic clique in the UCLA fine arts school based on painting. Photography, to them, was a mechanical, technological medium that did not involve the artist’s hand, and a lot of painters rejected it. It was not part of the fine art curriculum.

MS: It sounds like Heinecken was good at setting up an environment without many boundaries.

CC: Yes, while the whole tradition of black-and-white fine-art photo prints was well established in the art world. As students, none of us in those first classes were adhering to the Ansel Adams pictorial approach to photography. In fact, I think we were standing on Ansel Adams to start the department because nobody liked the Zone System approach that Adams represented. Heinecken was very free about that. I also remember the first moments when we were all sitting together [in the new photography department]. He was sitting on the table and said, “I don’t know what we’re going to do.” I thought that was the most honest thing I’d ever heard from any faculty member. It definitely was a fresh approach to the medium of photography.

Meanwhile, in the 1960s, there was a complete social and cultural upheaval in this country. As an Asian American who was raised slightly before the postwar baby boom, I saw what racist America was about. When you live in a place like San Fernando Valley, where there were only three Chinese families. In mine there were five boys, and we were popular kids. So it wasn’t like I was abused like an African American person who, at the time, couldn’t even go to the Valley without being followed by the cops. As the antiwar movement grew, it revealed a society fractured by racial, economic, and gender discrimination. Even having long hair meant that you were labeled a hippie and you could go to jail. To me, this was the dawn of multicultural America. Asians were always marginalized, but after that there was more acceptance.

MS: How did you come to make the pieces in Photography in Sculpture?

CC: I was making three-quarter-size car parts as photo objects at the time. I mounted the car parts on plywood and cut out the contour into a one-an-a-half-inch-thick photo object. There happened to be a molding machine in the industrial design shop, and I started playing with that in terms of a photo object. I just started putting them together and they seemed to work as sculpture. I took a photograph of an object and traced around its contour. Then I used that shape to cut a hole in the middle of a piece of plywood, which became the frame for the molding machine. I made two halves of a bubble with the same contour by flipping the plywood over.

MS: How did the photographs get laminated inside of the plastic?

CC: I put the film in between the plastic bubbles, glued the bubbles together, and trimmed the excess plastic. That’s it.

MS: So the film was not conforming to the shape? It’s flat inside the bubble?

CC: Right. It became another layer you looked through. I like the idea of looking through a number of flt images and seeing a three-dimensional object appear. At the time there wasn’t a film that you could photographically expose and then vacuum mold into a shape. If there was such a thing I probably would have used it. For me, at the time, I was just seeing if it was possible to make sculptural objects out of photography.

MS: Did Heinecken have much to say about plastic, or just the photographic elements?

CC: No. There was a lot more happening outside in society than whether I was using plastic or not. Even when we were students, we were taking pictures of the antiwar demonstrations, riots, Nixon, all that stuff. We would come back and store our film in the photo lab. The FBI came and was able to open selected lockers to confiscate all the film. There were a lot of upheavals in the school that related to anger about the Vietnam War, equal rights, women’s rights, et cetera. Anyone with any intelligence knew that we were only in Vietnam for political purposes. To me, that was more important than anything else, but when I looked around at UCLA, the faculty in the art department seemed unconcerned. They didn’t even relate to anything like that, which was very disappointing to me. I went into the glass studio at UC Berkeley and they were Pop art-like to me. By the time I made it, the San Fernando Valley looked like the United Nations. Every nationality seemed to live there. That, to me, was the most positive thing that happened during that time.

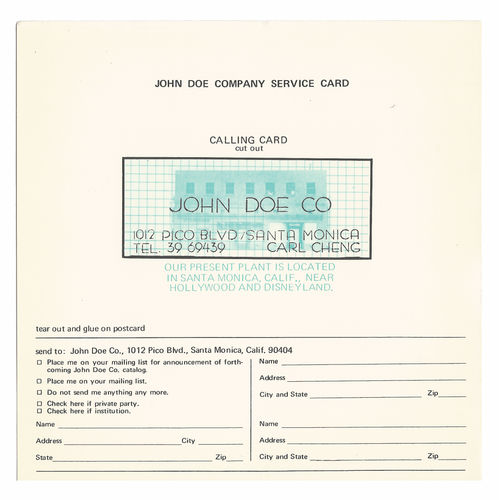

Most of my work hasn’t been just about my personal self, and by the early 1970s I’d taken on the mantle of AKA John Doe Co.

MS: How were you put in touch with Peter Bunnell for this show?

CC: Heinecken just said they were going to do a show. Bunnell came over, saw my work, and selected some.

MS: Were you impressed that somebody from MoMA was in Los Angeles? Was that important to you at the time?

CC: Of course it was flattering for the ego and self-worth. But that doesn’t last more than fifteen minutes.

MS: Were you interested in other artists who used plastic?

CC: Yes.

MS: Who during the late 1960s did you find interesting?

CC: Most of the teachers that I liked were not tenure-track but visiting artists, like Llyn Foulkes, and the sculptor Richard Boyce, who isn’t well known. Boyce made female genetalia out of clay. As an artist, you sometimes have a meeting of the minds with other artists. When you do, they become frieds for life. Heinecken was one of those kinds of guys. He didn’t have to tell me too much, and he accepted me. I felt that he was impressed with what I did, and that made him accept me as an artists. After every year he would write a review of what he saw in your work. He wrote some of the best comments I ever read. He had a way of talking about your work in a very humanistic way. I was moved by it. I thought he was a wonderful, sincere person.

MS: Did you see Photography into Sculpture?

CC: I thought I did, but looking back, I wasn’t even in the country at the time. In 1970 my girlfriend and I were already in Japan on a two-year trip that took us to Southeast Asia, Bali, and India. I returned to the United States in 1972.

MS: When you saw the restaging of the exhibition at Cherry and Martin, what was your overall impression?

CC: It’s hard to describe what that felt like. At the time, soon after making those specific pieces in the show, I would design, build, and install motorized sculptures, installations, water projects, and public art. That was my life. When I see these early accomplishments I think, “Oh yeah, that’s neat! Did I do that?” [laughing]

MS: Are you talking about your own work or more generally about the work in Photography into Sculpture?

CC: I’m just talking about myself. I mean, those other artists are independent artists. I knew some of them as classmates at UCLA, and after the show we all took off in different directions.

MS: Do you think Photography into Sculpturewas an important exhibition?

CC: Culturally speaking, it allowed for a more liberal idea of what a photograph could be, if nothing else. Otherwise, we might still be in the Ansel Adams pictorial school of photography.

MS: Its influence was temporary?

CC: I wouldn’t have expected it to be otherwise, given that Photography into Sculpturewas the title. Sculpture has been an institution since the caveman, you know. So it’s hard to say what is going to last as sculpture. In the MoMA show, sculpture is the giant elephant and photography is the technique around it. The title is transitory, and that’s what’s nice about it.

MS: What did you do afterPhotography into Sculpture? How long did you continue to make photo sculptures?

CC: I was still making the vacuum-formed photo pieces a year after I left school, even though I was working on other types of sculpture.

MS: You eventually started making public art projects. What about public art appeals to you?

CC: For complex reasons, I do not think of myself as a gallery artist. Some of my art projects could be sold, but I do not have a line of work or signature style that fits the cottage-industry concept. When the percent-for-art mandate was passed by most states, it created an opportunity for artists to compete for public commissions. I like making art that goes directly to the public. Using public money demands a certain responsibility, too. In public art you are given a sit, but it comes with politics, both social and cultural, that have to be deciphered. You then try to make something out of all of that. Visualizing something is what I like to do. Public art forces me to engage the public on a personal level.