There were a number of great presentations, but absent from this “revisiting” of the “Black Arts Movement” was the first nine years of activity that started in the Bronx in 1956 and quickly migrated to Harlem as it was influenced by the Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey as taught by Carlos A. Cooks and his African Nationalist Pioneer Movement (ANPM). The melding of Black political thought and the arts occurred during the Garvey years, but the contemporary movement that is widely thought of as the movement of the sixties, started in the summer of 1956, when seven young artists from the High School of Industrial Arts (SIA), now the School of Art & Design, Elombe Brath (Class of ’54), Kwame Brathwaite, Emilio Cruz, Andy Baron, and Frank Adu Robinson (Class of ’55) and Robert Gumbs and Bobby Diggs (Class of ’56) and several other young Bronxites, Al Young, Phillip Mungin, and the lone female, Shirley Anderson, all leaving their “doo wop” music past to graduate to more “progressive music” (before it was the “Boogie Down Bronx,” it was “The Be-Bop Bronx”). They began to embrace jazz and formed the Jazz-Art Society. Around about August 17, Marcus Garvey’s birthday, the Brathwaite’s started to draw close to the ANPM and the teachings of Garvey and African nationalism. (At this time in history, there was no other organization that had in its name “African Nationalist” or “African Nationalism” as its purpose. Elombe quickly moved to amend the name to African Jazz-Art Society, which met with opposition from some, but the militants prevailed).

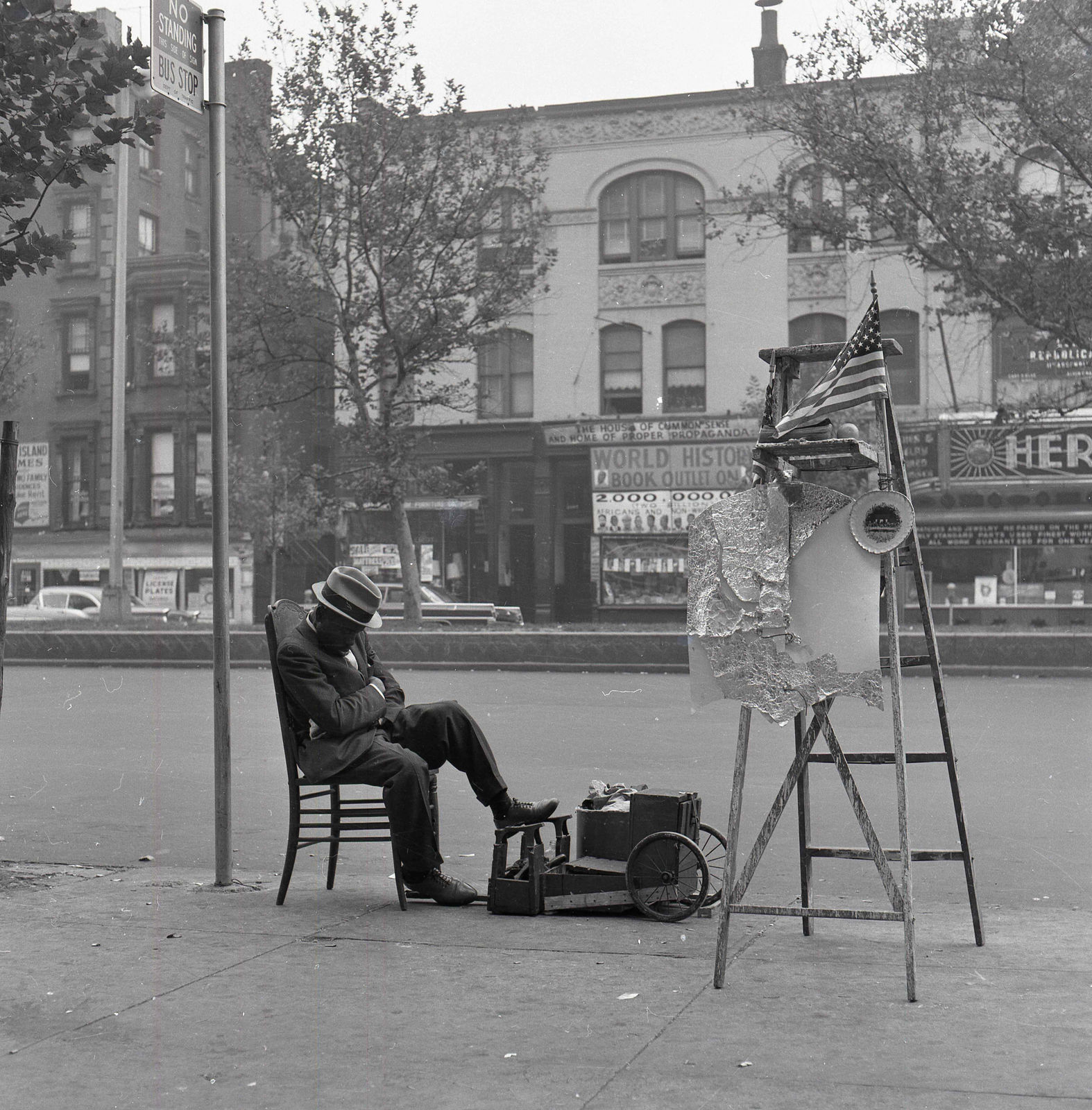

Using their artistic and promotional talents, they began to utilize the teachings of the ANPM lectures at the ANPM headquarters, and the street speakers at the corner of 125th Street and 7th Avenue and translate it into a form that those who would pass the street speakers ladder without bothering to listen would more readily receive the same thoughts as it was repackaged and fed back to them in an artistic form. AJAS produced its first jazz concert on December 24, 1956 at Small’s Paradise, with Lou Donaldson and the Bill English Quartet and a group of young budding jazz artists, George Braith, Bobby Capers, Vinnie McEwen, Oliver Beener, Pete LaRoca, Ray Draper and others. During those days, when you had a dance or music event in Harlem, there would be a break and there would be a “floor show,” which usually was a “shake dancer” or stripper. Instead of following the “norm,” AJAS ventured to the north Bronx, to 2404 Barnes Avenue, where a young African dance group led by Tina Potter auditioned for them, and were quickly hired.

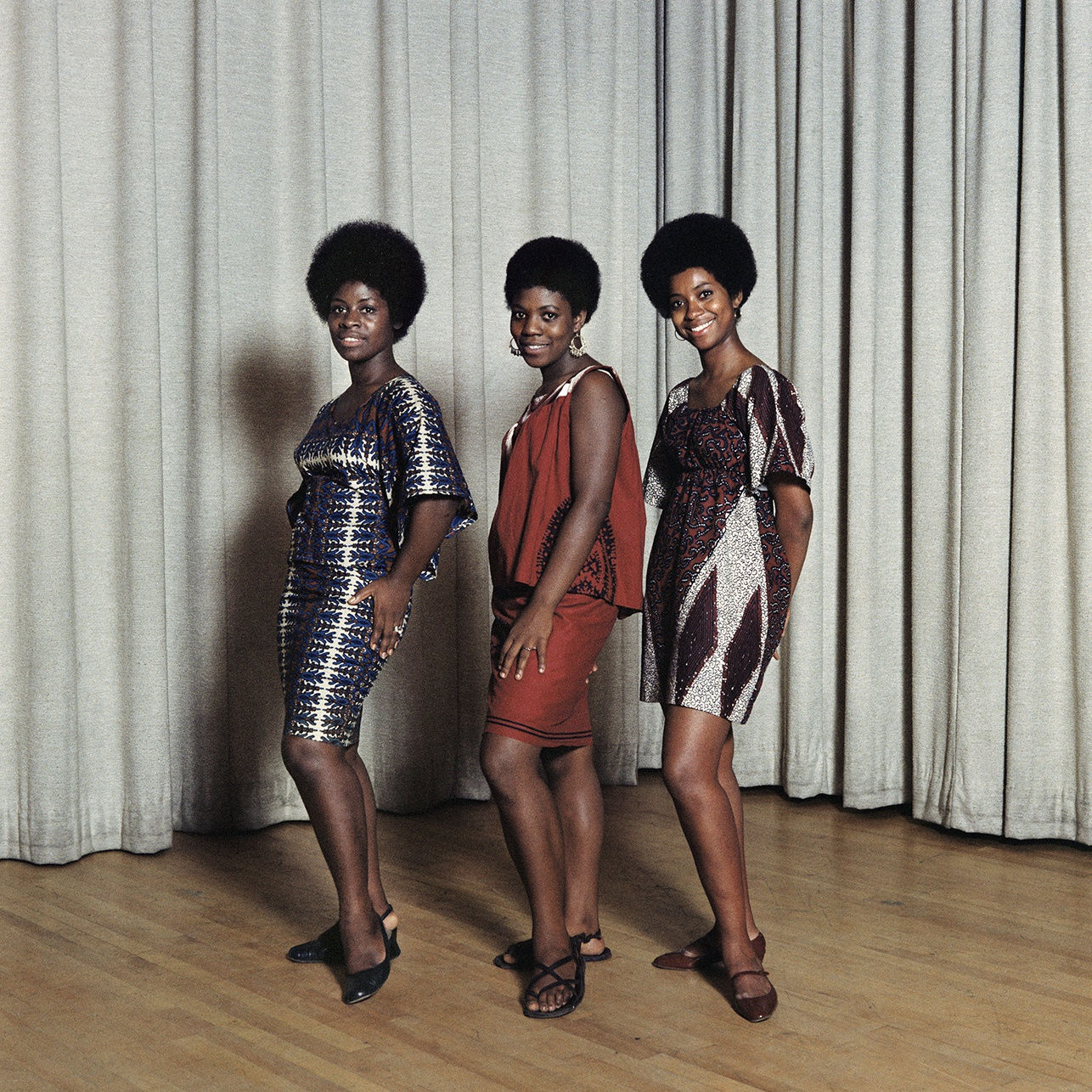

AJAS not only changed the model of club shows, but the graphic design of the advertising posters that announced the events. Prior to their artistic posters, events usually utilized block type, linotyped letterpress posters that left a lot to be desired. Designers, Elombe, Gumbs and then Milton Tuitt began to do layouts and designs for offset printing of the flyers and posters. They began politicizing the jazz artists, who were, although the great jazz stars of the day, were being underpaid and further disrespected in their accommodations and dressing room facilities, compared to the less capable and lesser known white musicians. AJAS used that formula until on August 17, 1961, at the Marcus Garvey Birthday Celebration, when during one of the featured events, “The Miss Natural Standard of Beauty Contest,” (a contest that was held every Garvey Day since 1942, one year after the founding of the ANPM, and two years after Garvey’s death), a young lady, named Clara Lewis – extremely Black and beautiful, won the title. The contest, in which the girls competed without make up and were required to washout any chemicals so that there hair was in its natural state, also asked the contestants questions on racial history, racial pride and tested how they thought about their people. The AJAS members had observed this contest year after year, and saw that by the time that the winner came to receive her $100 prize at the next Sunday night meeting, their hair was straightened again, since they didn’t feel that they could go to school or work without straightening it.

Elombe decided that we would put together a fashion show that would promote the natural beauty of our women. AJAS approached fellow promoter, Jimmy Abu, who was a male model, drummer and top-notch trainer of models, and AJAS began to recruit young ladies to train as for the group. AJAS moved its meetings from the Brathwaite basement in the Bronx, to a space they rented next to the Apollo Theatre, on October 1, 1961, and amended their name to the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios, adding art production, photo studio and rehearsal space and became AJASS. They devised a show which they called “Naturally ’62: The Original African Coiffure and Fashion Extravaganza Designed to Restore Our Racial Pride and Standards,” with the first show held at Harlem’s Purple Manor on January 28, 1962. The goal of the show was to prove to the world that “Black Is Beautiful.”

The first show starred Abbey Lincoln as guest singer and commentator for the show, and famed jazz drummer, Max Roach as Abbey’s accompanist on piano, Oluoju and Her Souls of the Earth African Dancers and Pucho and His Latin Soul Brothers band (who was the house band that offered us the space) and Jomo Logan providing some additional commentary on the African fashions.

The day of the show, the house was packed and people that couldn’t get in lingered outside. The show featured Clara Lewis, Black Rose, Nomsa White (now Brath), Priscilla Bardonille, Wanda Sims, Marie Toussaint, Esther Davenport and Beatrice Cranston, and male models Jimmy Abu, and Frank Adu, and actor Gus Williams opening the show with the models as he recited Marcus Garvey’s poem “Black Woman.” The show drew a standing applause and when the show was over and we looked outside, the crowd that couldn’t get in, was still there. We cleaned up the space and gave a second show that same day. The show was such a success, it inspired all of us and we planned for a follow-up show at a larger venue.

By now the word had gotten out, and people in the community were taking sides, pro and con. Some of the Harlem beauticians were up in arms, saying that the trend, if allowed to take hold, would take away a lot of their business. We booked a ballroom on 125th Street called the Sunset Terrace Ballroom for a follow-up show…If memory serves me right, this would be the first event at the newly renovated space.

Ticket sales were brisk for the new date, April 1, 1962, and we were sold out before the show. The morning of the show, we got a call from Jimmy Abu who was in Harlem and he told us that “the ballroom is on fire” and the firemen were chopping the place up. We rushed to the scene on this rainy “April Fool’s Day” and sure enough, the place was destroyed. Not to be outdone, I went to, first the Hotel Theresa, at 125th & 7th, which had a top floor ballroom and inquired, but to no avail, the room was booked. I went to the Celebrity Club, further east on 125th, which was also booked. I rushed up to Small’s Paradise, the venue of our first show eight years earlier, and asked what was going on in the ballroom that evening. They said “nothing,” and I said I wanted to book it. They asked, “for when?” I said, “for today!” They freaked out. I, being the treasurer, had the receipts for the sold-out event with me, and paid them on the spot. We stationed someone outside the burned out ballroom and someone on the phones at our studios as the phone kept ringing with people thinking the fire story was an April Fool’s joke.

As people came in cabs to the Sunset Terrace we told them, “don’t turn off the meter, go to Smalls. Miraculously we started the event only about one-half hour late, as the crowd came to the new location, in the pouring rain and our “fired up” crew gave a show even greater than we had expected. By now we had added some satirical skits, “Fantasy in a Barber Shop” being one of them, where actor David K. Ward comes into the barber shop to get his hair “conked,” (i.e. straightened). This pantomimed skit was hilarious and thus we successfully combined art, music, fashions, dance, acting, poetry and comedy into political “edutainment.” We named the models, The Grandassa Models, the name Grandassa taken from Grandassaland, one of the many names for Africa before the time of the great erosion, when the continents of Africa and Asia split. This was 1962 and a movement encompassing all of the arts had begun. AJASS and the Grandassa Models, and the AJASS Repertory Theatre Company, (later to be renamed the AJASS Griots) formed a production that began to play various New York venues before taking to the road. The Sunset Terrace was never rebuilt and nothing took place on that site until last year when a new structure was erected.

We played the Fez Ballroom in Brooklyn, the “It’s Time” concert with Max Roach Orchestra and Chorus with Abbey Lincoln, and Coldridge Perkinson conducting in a benefit show trying to save a Black private hospital, the Mount Morris Park Hospital, and began looking for larger ballrooms. The cry “Black Is Beautiful” began to be heard throughout the city.

During their travels, Max and Abbey contacted progressive brothers and sisters in Detroit and Chicago and helped us book the show in those cities. We arranged a show in New York at The Audubon Ballroom for January 17, shows in Chicago at Roberts Show Club on February 22, and one at Mr. Kelly’s in Detroit on February 23, 1963, and took the show on the road. In Detroit, LeRoy Mitchell and Omar Shabazz, two art students at Wayne State University, were absolutely fabulous. They decorated Mr. Kelly’s with replicas of the Grandassa Model logo, a silhouetted black head in profile, with a Nefertiti-like hairstyle. Both Mitchell and Shabazz went to live and teach in Ghana.

In Chicago, the beauticians were far more progressive than those in Harlem. I went to Chicago after our January show to promote the upcoming event. Beauticians invited me to come to a beauty school and show the slides of the shows and the hairstyles, and they began to add our natural hairstyles to the hairstyles that they offered. I received such welcome and help from all areas of the Black community. I even went into bars and was allowed to set up my slide projector and show images of the shows and the models, fashions and hairstyles. I would never have the opportunity to do that, even in our home base in Harlem.

I had met a photographer in New York at the Randall’s Island Jazz Festival in 1959 or 60, when we both were photographing the festival. He was from Chicago. His name was Funde Abernathy. I remembered that I had his card and dug it out before going to Chicago. When I contacted him, he informed me that his father had a cab company, the Abernathy Cabs, and they put cars at my disposal, often at no charge for the time that I was out there. Funde later came to Harlem in about 1965, when Amiri Baraka came to Harlem and formed the Black Arts Repertory Theatre. With him came several white women from the village. They were quickly run out of Harlem by the sisters.

Needless to say, both shows were successes, but sparked more controversy. That was the first of our road shows, that later took us to Lincoln University where a Black student group which included by Sam Anderson and Gloria Dulan-Wilson; Cornell University where Brother Makaza (a.k.a. Herbert Callendar) sponsored the show; North Babaylon for the National Council of Negro Women, among other places, spreading the nationalism and art that traversed the globe.

In 1963, Herbert Manangatheri, an editor of eleven African newspapers and African Parade Magazine, publications that were printed and distributed in the still colonized countries then known as Northern and Southern Rhodesia (Zambia and Zimbabwe) and some neighboring territories, visited our 125th Street studios with Max and Abbey. He interviewed us and I gave him photos of the Grandassa Models and some of our brochures and press material. Soon after he ran three successive cover stories in African Parade Magazine about the show, the first and third of the issues featured Grandassa Models on the cover, and the issue in-between them featured Abbey Lincoln on the inside cover. We read an article describing how they copied the show in Lusaka (Zambia), and a campaign began to replace the images that were coming from what they saw from Black publications in the US, that featured Black women wearing blonde and red wigs, “candy” lipstick and “hot pants,” with a natural image like the Grandassa Models and our African fashions. In the magazine they reported that bands of Black youth were snatching wigs off of the heads of the African girls that were adopting what we called the “Congo Blondes and Zulu Redhead” styles, and wiping their lipstick off with sandpaper.

In 1963, AJASS formed The Black Standard Publishing Company, which created two publications, The Naturally ’63 Portfolio and the now collector’s item, “Color Us Cullud: The Official American Negro Coloring Book,” written and illustrated by Elombe Brath. The book targeted the weaknesses of the civil “rites” movement and their non-violent, turn the other cheek, integrationist policies. The last thing that Malcolm X said to me directly was “tell your brother he’s a genius,” referring to Elombe’s analysis in the book, of the ban that Malcolm was under and the source of the problem.

Abby performed with us until the fall of ’64 when she left to go to Hollywood to star with Ivan Dixon in “Nothing But A Man” one of the most important Black films of all time. By then, with her and Max’s help, the production had been so popular we were able to dare book the largest ballroom in Harlem, Rockland Palace which held 4,200 people. We set our shows banquet style, to seat 1,500 or so people and used the rest of the floor for our show. We packed it each time through Naturally ’78, performing usually two large shows in New York each year, while AJASS produced other theatre productions, “Caste Life Revue” and “A Portrait of Patrice Lumumba.” The “Naturally” shows drew many of the top artists. Even Nina Simone and Miriam Makeba came to one of the events together.

This year, AJASS is celebrating its 50th anniversary. The Naturally shows alone lasted 16 years, and AJASS nine years before and the Black Arts Repertory Theatre was formed in Harlem, and eleven years after they left. They, Baraka, Larry Neal, Ed Bullins, et.al, did some great work in the short time that they were in Harlem, but an honest review of the record should reflect the true history of the Black Arts Movement from AJASS, to The 20th Century Art Creators (1964), which became the Weusi Nuymba ya Sanaa (Swahili for “House of Black Art”), 1965 and now celebrating their 41st anniversary – all before the arrival of Baraka’s Black Arts Repertory Company. They started the outdoor art shows in Harlem. Likewise the Benin Gallery and Grinnell Gallery get no mention in these scholarly meetings which compromises their accuracy.

At the colloquium and in most of the writings on the “Black Arts Movement,” “Black Is Beautiful” is mentioned in passing, but no one mentions its importance or how it started or when it was born. We can assure you that it was not like Topsy in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. When she was asked when she was born, she answered, “I wasn’t born…I just grew up.”