For over 50 years, the photographer Kwame Brathwaite captured African-American beauty and fashion, giving visual power to black power.

The intersection of West 125th Street and Seventh Avenue in Harlem was, for decades, a center of black nationalism. Street orators - that's what they were called - climbed onto stepladders and made impassioned calls for African liberation.

When Kwame Brathwaite and his brother Elombe Brath were teenagers in the 1950s, they would walk there from their dad's dry cleaning shop and listen, entranced, for hours. Mr. Brath once recounted the story of Carlos Cooks, a student of Marcus Garvey, bellowing to a black woman walking by: "Your hair has more intelligence than you. In two weeks, your hair is willing to go back to Africa and you'll still be jivin' on the corner." (Two weeks was just about how long hot-combed styles kept a black woman's hair straight.)

After a few years of standing rapt at that corner, the brothers helped found the African Jazz Art Society and Studios, an artist collective also known as AJASS. The group produced concerts "to promote awareness of African-derived black music and dance forms," Tanisha C. Ford, a historian, wrote in her book "Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul."

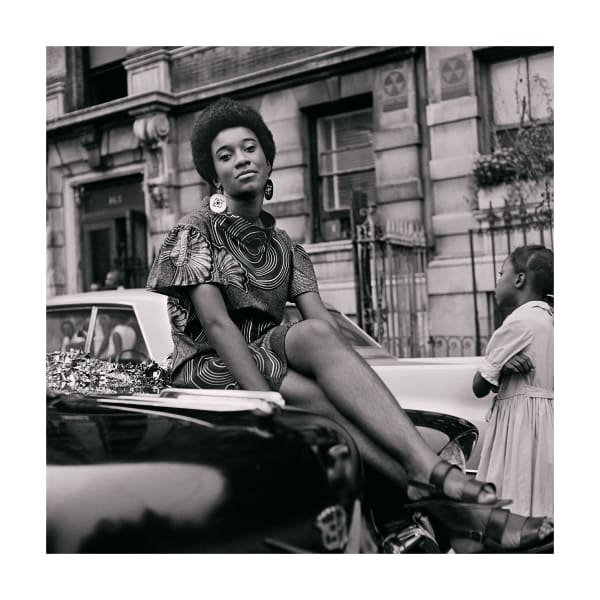

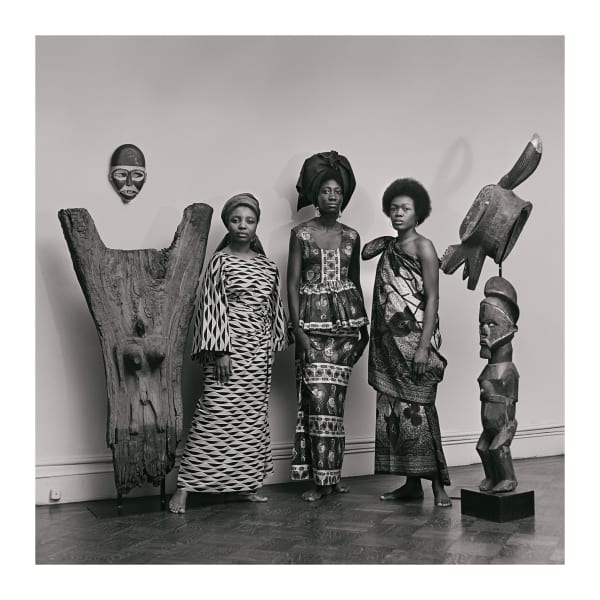

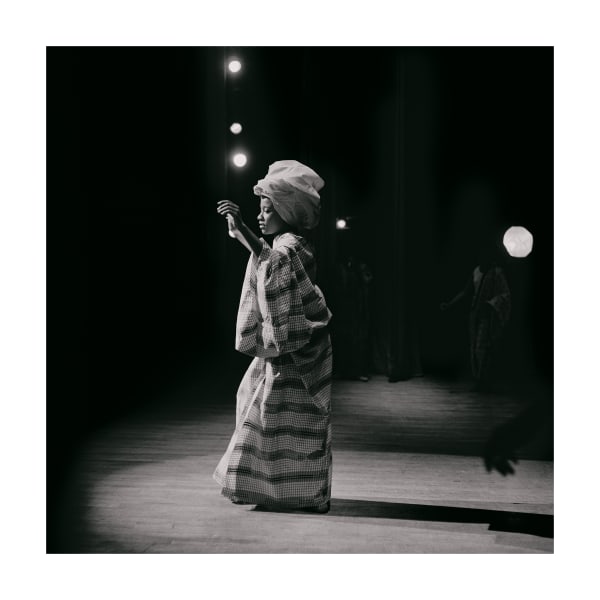

It was with AJASS that Mr. Brathwaite started his career in photography, taking pictures first of the artists at the shows and then of residents of Harlem generally. AJASS later expanded its arts activism to include the Grandassas - black women the group recruited to model. Black women with kinky hair, full lips, dark skin, and curvy bodies. Black women who could show other black women that blackness was something to take pride in.

Kwame Brathwaite documented them all.

"Kwame Brathwaite: Celebrity and the Everyday," at the Philip Martin Gallery in Los Angeles, features Mr. Brathwaite's images of the Grandassas. They were women who connected their natural hair to their politics - some sheepishly, yet with increasing feelings of empowerment when fashion show audiences cheered for them; and others proudly, as activists already invested in the politics of black beauty.

The show also includes images of celebrities like Muhammad Ali and Stevie Wonder, both of whom Mr. Brathwaite had befriended through his work as a photographer.

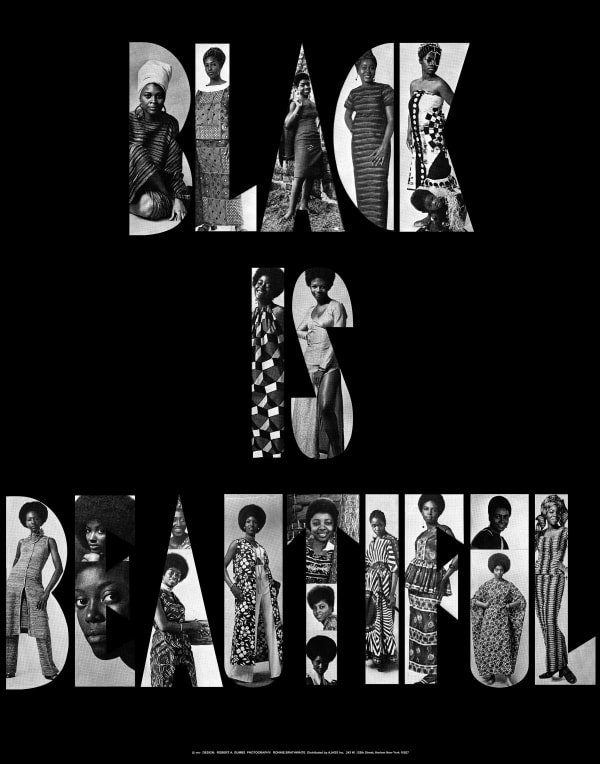

Black Power has been considered the more militant race reform effort, emerging as a splinter group from civil rights, and aligning more closely with black nationalism. 'Black is beautiful' became its slogan, widely hailed in the mid-1960s by its artists-activists belonging to the Black Arts Movement. A lot of the early contributions to the Black Arts Movement, like Mr. Brathwaite's, got lost in this parsing of ideologies. But scholars have now positioned the black power movement alongside the civil rights movement, noting their overlapping concerns and shared visions.

Looking at Mr. Brathwaite's photographs today feels like thumbing through a scrapbook of ads from the "Mad Men" era - except that everyone in them is black. To some extent, black power's effectiveness as a political slogan owes a debt to how Mr. Brathwaite showcased his subjects. In 1962, when AJASS organized its first fashion show, Naturally '62, in the basement of a Harlem nightclub, "people showed up, en masse," Ms. Ford, the historian and author, told me, "but largely because they were skeptical. Because they wanted to see how it was going to go: What are these women going to look like?"

Even some black nationalists among them didn't wholeheartedly support AJASS's efforts, particularly the Naturally fashion shows. "There were black men at the time, who could believe the teachings of Marcus Garvey, but still preferred blackness to show up in the form of straight hair on a black woman," Mr. Ford said. "Then there would have been other men in that community who would have said, 'These are the most beautiful women walking.'"

AJASS leveraged its relationships with jazz greats and black nationalists Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach to get more attention for the group's work with the Grandassas. "It's a big part of how the 'Black is Beautiful' message got out to the public," Philip Martin, the gallery's owner, said. "It became a household phrase before people even knew where it originated."

The Naturally show became so popular it went on the road, traveling to the Midwest to affirm a "black is beautiful' message that was barely evident there. The Grandassas appeared on jazz album covers and booked ad campaigns for African and Caribbean magazines.

In her book "The Global Beauty Industry: Colorism, Racism, and the National Body," which examines beauty through the lens of gender and race, Meeta Rani Jha saw the Black Is Beautiful movement as a watershed moment. "If femininity is defined by the absence of blackness," she wrote, "then the role the Black Is Beautiful movement played is one of the most significant anti-racist challenges to the dominant white beauty, destabilizing its cultural power."

And Kwame Brathwaite helped start it. He and his brother understood back then, years before hair and beauty became strongly associated with black politics, that people, sometimes even black people themselves, were blind to how black is beautiful.

Mr. Brathwaite encouraged these messages for more than fifty years. They have even more potency today.

"It's really, really, really important to lift up actual black beauty, black images, dark-skinned people," said Jesse Williams, the actor, who curated the show along with Mr. Brathwaite's son. "It's still very, very rare to see them in that light."