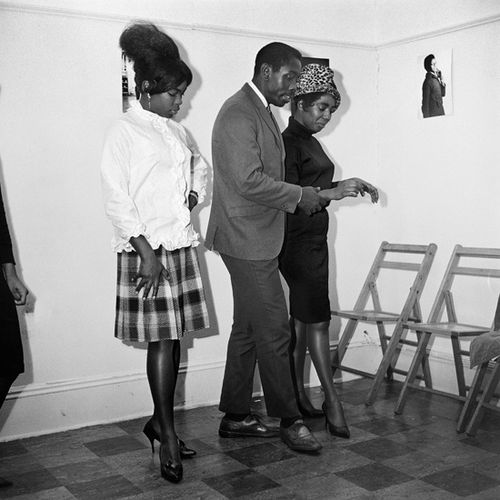

On the night of January 28, 1962, in a small Harlem nightclub called the Purple Manor, a show took place that would end up igniting a global movement. Known as “Naturally ’62,” the event was billed as “the original African coiffure and fashion extravaganza,” featuring an all-black cast of models resplendent in Afrocentric designs and natural hairstyles and performances by jazz musicians Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach. “The line to get in was so long we ended up clearing the venue and doing a second show,” says photographer Kwame Brathwaite who conceived of the idea with his late brother, Elombe Brath. As cofounders of the African Jazz-Art Society and Studios, or AJASS, a collective of creatives that included Lincoln and Roach, the brothers were part of a growing community of Pan-African activists inspired by pioneering black thinkers such as Marcus Garvey and Carlos A. Cooks. Their “Naturally” events were a glorious celebration of a new African-American style identity, one that gave rise to the rally cry Black Is Beautiful.

“Walking in those shows was amazing and affirming,” says Brathwaite’s wife Sikolo who joined Grandassa models, the agency launched by her husband and brother-in-law, in 1966. “Many of the models made their own clothes. It was really about doing our own version of traditional African clothing.” In one of the most striking portraits in Brathwaite’s series—a selection of which is currently on view at the Museum of the City of New York until April 1—Sikolo is wearing a spellbinding beaded headpiece by Carolee Prince, the woman behind many of Nina Simone’s most iconic looks, that brings to mind Yoruban royalty. In another, her glossy black Afro fills the frame like an elegant crown. At the time, the photographer was best known for his candid reportage of black celebrities—Grace Jones, Nina Simone, Muhammad Ali—though it’s his pictures of the Grandassa models that have the strongest resonance with now. You can easily imagine Brathwaite’s portraiture sitting comfortably next to the vision of black female empowerment evoked by artists such as Solange Knowles and Erykah Badu, for example. Indeed, his “Black Is Beautiful” series will be the subject of a panel discussion next week: Brathwaite’s son, Kwame, will sit as a panelist alongside his 80-year-old father, and designer Mimi Plange.

“Back then everything on the newsstands was Eurocentric. There was no Essence,” says Kwame, who began digitally archiving his father’s work last year, putting it before a wider audience for the first time. “My father gave the movement a visual language that had never existed.” (Incidentally, Brathwaite would end up shooting his wife Sikolo for the cover of Essence in 1974, when she was pregnant with Kwame, Jr.) Now, many of the previously unseen pictures have gotten the attention of the art world—he was honored at Aperture’s annual gala last October and has a book is in the works. For the photographer, the most exciting response has come from a new generation of politically conscious black women who are discovering his work for the first time. “Looking back on that time, I remember every second of it. There was so much joy in making those shows. It was all about cooperation and working together,” says Brathwaite. “My goal was always to capture the beauty of black women, to restore black pride and the spirit of black women.”