In her new series for Roman Road Journal, Philomena Epps explores various facets of contemporary performance and video art by women artists through the lens of current exhibitions. In the second instalment, she looks at a pair of exhibitions by Marianna Simnett and Ericka Beckmann currently on view at the Zabludowicz Collection, exploring how the body is mythologised, historicised, or pathologised.

How is the body mythologised, historicised, pathologised? The Zabludowicz Collection in London has programmed two concurrent solo exhibitions from artists Ericka Beckman and Marianna Simnett, who engage with these questions in their practices. Despite appearing initially divergent, there are productive crossovers between use of moving image, performance, and the mythology that surrounds ideas of female corporeality, identity, and desire. Beckman, who is based in New York, has established a unique, filmic language in her work that often employs the structure of games, in order to examine the impact of technology on the construction of gendered identities. Other themes include the precariousness of labour, the embodiment of architecture, and the nature of post-industrialised society. Simnett is based in London. Her interest in technology is similarly centred within notions of the industrial, but also focused on the bio-medical and surgical, and often converges with child-like fantasies, instances of instability or hysteria, and the corruption of the body. Both artists engage with the impact of new technologies—gaming culture, robotics, medical or cosmetic developments—on their protagonist’s subjectivity or objective environment.

Beckman’s exhibition opens with the two-screen installation Hiatus (1999/2015), a prescient anticipation of the social and cultural impact of video gaming and online networks. Beckman began making the film in the late 1980s, working alongside computer scientists at the NASA Ames Research Center (in a still emerging Silicon Valley), to understand the latest developments in computing technology, interactive games, and virtual reality. The narrative applies the learning and competitive structure of games as a means to reveal the conditions of gender and identity formation. To quote Beckman, the work is “an experimental narrative film about a young woman who plays Hiatus, an online interactive ‘identity’ game. Propelled through action by her Go-Go cowgirl construct Wanda, and powered by a computer corset that stores her programs in a garden interface, Maid meets Wang, a powerful take-over artist. She must learn how to use the power of her ‘organic memory’ to block his expansion and preserve her freedom.”[i] The word ‘wang’, an obvious slang synonym for penis, derives from the less obvious 1930s phrase ‘whangdoodle’, an earlier term for a ‘gadget’. The World Wide Web becomes, quite literally, a competitive field for gendered and corporate rivalry. Beckman’s foresight is acute—particularly in this moment of data breaches and leaks— in relation to how the utopian nature of the Internet has been relentlessly abused by bureaucracy and the hegemony of neoliberal politics.

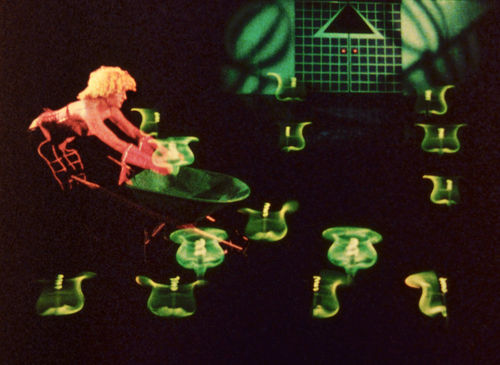

Constructed in early CGI, the aesthetic of the work—a black-box space, strips of neon, objects and costumes cast in bold primary hues—is akin to the design and colour scheme of video and arcade games. In addition to a heightened sense of masquerade and role-play, Beckman litters the scene with common symbols associated with fairy tales— magic beans, inanimate objects (totem poles) and animals (birds) giving warnings, a scarecrow, etc—but grounds them within this hyper-real proto-digital space, complete with architectural blueprints, checkerboard floors made from memory chips, and looming electricity towers.

Work by artists such as Reija Meriläinen or Rachel Maclean, could be brought to bear in relation to Beckman’s use of game structures and fantasy narratives as a way to critique contemporary culture and destabilise societal power dynamics. Meriläinen’s video game installation Survivor (2017) was commissioned as part of the ‘ARS17’ group show, at Kiasma in Helsinki, which focused explicitly on how the digital revolution has affected contemporary art. Throughout the dystopian game, the player is forced to make decisions based on social politics and snap judgements. The quick, cut-throat nature deconstructs how hierarchies and social cliques function in everyday encounters, and belies a deeper sense of structural violence: “your goal is to outcast players, and you can learn how to do it in real life.”

In Maclean’s Spite Your Face (2017), which debuted at the Venice Biennale last year, the Pinocchio-like protagonist was an explicit response to the divisive campaigns in the lead up to the Brexit vote and the US Presidential election. In Maclean’s words, the character “rises from a deprived social status to the heights of power by constantly lying. Meanwhile, those around him celebrate the grotesque physical consequence of telling untruths – his increasingly large nose. This is a darkly comic moral tale for a generation that has increasingly fewer role models to set the ethical standard.”[ii] Maclean is an artist fascinated by how the grotesque has been used to satirise political figures or ideas of social class throughout history, from William Hogarth to The Fast Show. Her earlier work similarly subverted celebrity culture, children’s television, and beauty advertising, as a means to create a satirical parody of how technology and social media is exacerbating anxiety, encouraging rampant individualism, and establishing a world of dangerous binaries.

The fairy tale has been an important resource for a host of artists working within the realm of feminism and performance, such as Joan Jonas —significantly The Juniper Tree (1976) and Upside Down and Backwards (1979), the former currently on show at Tate Modern—and Cindy Sherman. Despite not replicating specific stories, Sherman’s macabre series Disasters and Fairy Tales (1985-89), used imagery appropriated from the Brothers Grimm, folk legends, and fable mythology, but also combined them with more disturbing, acerbic scenes depicting food, waste, and vomit. As a New York Timesarticle from 1985 testifies, these images were occasioned “by an assignment from Vanity Fair magazine to illustrate children’s fairy tales … [however] Miss Sherman’s new pictures failed to make their way into print as intended.”[iii]

Similarly, in a literary vein, writers like Angela Carter subverted the traditional notion of women as an object of exchange in her fiction, using the form of magical realism, and the motif of metamorphosis to instead liberate her protagonists from conventional gender roles. “I’m in the demythologising business,” she wrote in an essay titled Notes From the Front Line (1983), “all myths are products of the human mind, they are extraordinary lies designed to make people unfree.”[iv] By deconstructing the male gaze in order to twist the latent aggression and violence that is implicit in our visualising practices, Carter rejected the fantasy projected on the female body as an object of male gratification, working towards a total re-appropriation of the figure of woman. Her renowned collection of short stories The Bloody Chamber (1979), were explicit re-writings of traditional fairy tales, inspired by the work of the French author and so-called ‘father’ of the fairly tale Charles Perrault (1628-1703). Perrault was known as the ‘father’ of the fairy tale, which he had refigured from existing folk stories.

Perrault is the original writer of the Cinderella (Cendrillon) story, which Beckman takes apart in her 16mm video Cinderella (1986). “A musical treatment of the fairy tale,” she wrote in 1984, “I have broken apart the story and set it as a mechanical game with a series of repetitions where Cinderella is projected back and forth like a ping-pong ball between the hearth and the castle. She never succeeds in satisfying the requirements of the ‘Cinderella Game’.”[v] Beckman worked in collaboration with Brooke Halpin to compose the soundtrack, using the tones and rhythms of contemporary experimental music, repetitions of playground chants, and the narrative voice of a Greek chorus. Sound operates as a pre-linguistic tool for communication. Akin to the use of a game structure in Hiatus, Beckman utilises the construction of an arcade slot machine as a form of linear narrative. She also subverts the ‘damsels in distress’ archetype. The heroine refuses to follow the rules of the game, therefore forfeiting her prince, and establishes a new allegorical path: independence, female determination, and self-fulfilment.

Beckman’s dream-like narrative and analysis of interior space is particularly pertinent when thinking about the trilogy of visceral, horror-cum-musical films— The Udder (2014), Blood (2015) and Blue Roses (2016)—exhibited by Marianna Simnett at Zabludowicz. Sound is configured as a pre-linguistic tool for communication. Simnett writes songs for her cast (often untrained actors) to perform. The catchy repetitions and haunting numbers provide cathartic light relief, despite acting as moral cautions and laments. Akin to Carter’s fiction, the narrative of the films appropriates the morality of magical realism, in order to examine the desire for, and control of, female bodies in the social construction of identity. Themes of childhood innocence, chastity, sexuality, and purity intersect in dizzying, often harrowing, ways. Carter packed The Bloody Chamber full with mythology and gendered symbols that troubled the economy of the visual field, exposing how women operate within the male fantasy: there is sadomasochism, fatal passion, red meat, animal fur, snow, menstruation, mirrored hotel room ceilings, jewels, and an emphasis on naked flesh. Simnett’s perverse tales of consumption and corruption offer similarly unflinching depictions of dark fantasies—her signifiers include bodily fluids, blood, milk, internal organs, prosthetics, insects—but they are merged with scientific descriptions and procedures, presenting the body as abject and monstrous, but also eerily clinical, subjected to violence, cruelty, or medical operations.

All three films exude a monstrous intimacy. The Udder is predominantly set within the cow’s mammary gland, which is infected with mastitis, a bacterial disease that affects bovine mammary glands. Blurring animal and human parts, teats become a tongue, phallus, finger, and nose. In The Blood, the removal of turbinate bones in the nose—a procedure for persistent nosebleeds and headache—is based on a botched operation performed by Wilhelm Fleiss on Emma Eckstein (one of Sigmund Freud’s patients), which left her disfigured. Fleiss believed that the cause of women’s ‘hysteria’ was a link between the nose and genitals, often cauterising nasal glands as a cure for menstrual cramps. A cosmetic procedure, the removal of varicose veins on the back of a knee, dominates the narrative of Blue Roses, which is seen through the perspective of the disembodied leg. Interrupted by scenes shot in a Texas laboratory, we see students attempt to control the movement of cockroaches, through shocking them with cruel electric signals.

In conversation with writer Charlie Fox for Mousse Magazine, Simnett noted, “It starts with an exploration of parts you can’t see without an aid or an other. Horror Zones. Like the back of the knee in Blue Roses or the tip of the nose in The Udder. And then I like to look inside and see what you’re not normally allowed to see … Piercing what seems rigid or solid or performing mutations of bodies and gender.”[vi] In The Needle and the Larynx (2016)—a later work, not on show at Zabludowicz —Simnett filmed herself having Botox injected into the cricothyroid muscle in her throat in order to surgically lower her voice, while reciting a surreal three-part parable about a girl who wants a surgeon “to make [her] voice low so that it trembles with the earth and is closer to those groans outside that keep [her] turning in the night.”

It is intriguing to think about Simnett’s creation of an active and autonomous female body within the medical sphere, in relation to the work of the controversial French artist ORLAN. In 1990-1993, ORLAN undertook a series of nine ‘performance-operations’, inspired by the classical beauty ideals derived from Western art. Under the umbrella title of The Reincarnation of Saint-Orlan, her aim was to transform her own physical body into various guises, a chin like Botticelli’s Venus, the nose of Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Psyche, the lips of Boucher’s Europe, the eyes of Diana as painted by the Fontainebleau School, and the forehead of Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. ORLAN’s seventh ‘performance-operation’—Omnipresence (1993)—was broadcast live from Sandra Gering Gallery in New York by satellite to fifteen different art institutions across the world. Spectators were able to ask her questions, and there were extra personnel on hand to translate into English and sign for the deaf. Through this deliberate overturning of the expectations of cosmetic surgery protocol, a usually clandestine experience, ORLAN claimed autonomy as an active patient. Similarly, through refusing general anaesthesia, she retained “ultimate (conscious) control of the process of her facial remoulding and thus the representation of her (female) face and body in art.”[vii]

With the female body at their core, Beckman and Simnett’s films can be seen to subscribe to Carter’s “demythologising business”, by destabilising and denying these precarious and patriarchal notions of ‘woman’. Either flipping the switch and short circuiting the narrative, in the case of Beckman, or subverting to the point of absurdity, degradation, and repulsion, in the case of Simnett. Their unique approaches to mythology and storytelling—drawing upon archetypes and fairy tales—indicate the construction and fantasy that surrounds gender, and its entrenchment within coming-of-age parables, and the mutual mechanisms of desire and consumption.

—

[i] Ericka Beckman, ‘Hiatus’ (1999), from the artist’s website

[ii] Rachel Maclean, Spite Your Face (2017), from the artist’s website

[iii] Andy Grundberg, ‘Cindy Sherman’s Dark Fantasies Evoke a Primitive Past,’ in the New York Times (October 1985)

[iv] Angela Carter, ‘Notes from the Front Line,’ in Critical Essays on Angela Carter, ed. Lindsey Tucker (G.K. Hall & Co, 1998) p.25

[v] Ericka Beckman, ‘Cinderella’ (1984), from the artist’s website

[vi] ‘Hazmat: Charlie Fox and Marianna Simnett,’ in Mousse (2017)

[vii] Tracey Warr, ‘ORLAN’, in The Artist’s Body (Phaidon, 2012) p.185

—

Exhibitions by Marianna Simnett and Ericka Beckmann are at the Zabludowicz Collection until 8 July 2018. Read more here.

Philomena Epps is an independent writer and art critic based in London. Her writing has been published by Apollo Magazine, Art Agenda, ArtAsiaPacific, ArtForum, Art in America, Elephant, Frieze, MAP, The White Review, and more. She is also the founding editor and publisher of Orlando.