-

In Conversation with Sky Glabush

July 26, 2024 -

Sky Glabush, Mount Temptation, 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 24 x 18 in; 61 x 45.7 cm

Sky Glabush, Mount Temptation, 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 24 x 18 in; 61 x 45.7 cm -

-

Sky Glabush, Rain (Study), 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 11 x 14 in; 27.9 x 35.6 cm

Sky Glabush, Rain (Study), 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 11 x 14 in; 27.9 x 35.6 cm -

Sky Glabush, Pictures of You, 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 16 x 12 in; 40.6 x 30.5 cm

Sky Glabush, Pictures of You, 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 16 x 12 in; 40.6 x 30.5 cm -

-

Sky Glabush, Logging Road at Night (Study), 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 16 x 12 in; 40.6 x 30.5 cm

Sky Glabush, Logging Road at Night (Study), 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 16 x 12 in; 40.6 x 30.5 cm -

Sky Glabush, Lavender Light, 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 11 x 14 in; 27.9 x 35.6 cm

Sky Glabush, Lavender Light, 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 11 x 14 in; 27.9 x 35.6 cm -

Sky Glabush, Burning (Study), 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed with Optium Museum Plexiglas, 21 x 18 in; 53.3 x 45.7 cm

Sky Glabush, Burning (Study), 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed with Optium Museum Plexiglas, 21 x 18 in; 53.3 x 45.7 cm -

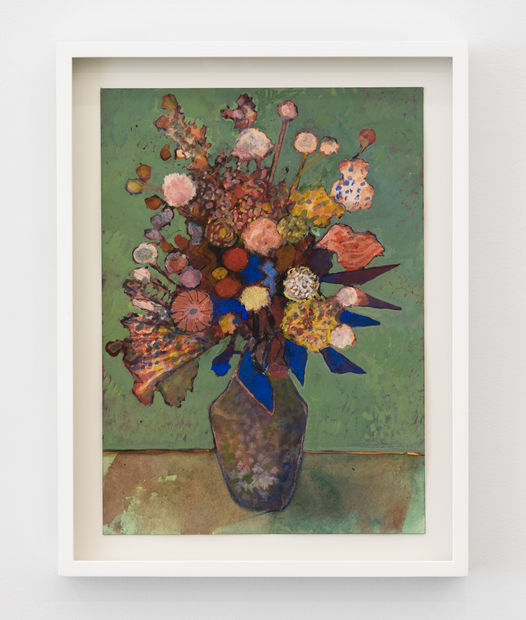

Sky Glabush, Flower Study (After Redon), 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed with Optium Museum Plexiglass, 14 x 10 in; 35.6 x 25.4 cm

Sky Glabush, Flower Study (After Redon), 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed with Optium Museum Plexiglass, 14 x 10 in; 35.6 x 25.4 cm -

-

![['Branches in Light'] is a wonderful winter painting, do you want to talk a little bit about it? I always...](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Sky Glabush, Branches in Light, 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed with Optium Museum Plexiglass, 12 7/8 x 10 7/8 in; 32.7 x 27.6 cm

Sky Glabush, Branches in Light, 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed with Optium Museum Plexiglass, 12 7/8 x 10 7/8 in; 32.7 x 27.6 cm -

-

Sky Glabush, The Sun's Escape, 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 14 x 11 in; 35.6 x 27.9 cm

Sky Glabush, The Sun's Escape, 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, unframed, 14 x 11 in; 35.6 x 27.9 cm -

Sky Glabush, Red Forest Interior (Study), 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed with Optium Museum Plexiglass, 12 x 16 in; 30.5 x 40.6 cm

Sky Glabush, Red Forest Interior (Study), 2024, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed with Optium Museum Plexiglass, 12 x 16 in; 30.5 x 40.6 cm -

-

Sky Glabush, Above as Below, 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed, 10 x 14 in; 25.4 x 35.6 cm

Sky Glabush, Above as Below, 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed, 10 x 14 in; 25.4 x 35.6 cm -

Sky Glabush, Ocean at Night, 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed, 10 x 14 in; 25.4 x 35.6 cm

Sky Glabush, Ocean at Night, 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed, 10 x 14 in; 25.4 x 35.6 cm -

Sky Glabush, River Through Trees, 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed, 24 x 18 in; 61 x 45.7 cm

Sky Glabush, River Through Trees, 2023, Watercolor and gouache on paper, framed, 24 x 18 in; 61 x 45.7 cm -

-

Sky Glabush, Zermatt Landscape 1, Mountain Lake (study), 2023, Watercolor on paper, unframed, 8 x 10 in; 20.3 x 25.4 cm

Sky Glabush, Zermatt Landscape 1, Mountain Lake (study), 2023, Watercolor on paper, unframed, 8 x 10 in; 20.3 x 25.4 cm -

Sky Glabush, Zermatt Landcape 2, 2023, Watercolor on paper, unframed, 8 x 10 in; 20.3 x 25.4 cm

Sky Glabush, Zermatt Landcape 2, 2023, Watercolor on paper, unframed, 8 x 10 in; 20.3 x 25.4 cm -

Sky Glabush, Zermatt Landcape 3, 2023, Watercolor on paper, unframed, 8 x 10 in; 20.3 x 25.4 cm

Sky Glabush, Zermatt Landcape 3, 2023, Watercolor on paper, unframed, 8 x 10 in; 20.3 x 25.4 cm -

Sky Glabush, Zermatt Landcape 4, 2023, Watercolor on paper, unframed, 8 x 10 in; 20.3 x 25.4 cm

Sky Glabush, Zermatt Landcape 4, 2023, Watercolor on paper, unframed, 8 x 10 in; 20.3 x 25.4 cm

-

Sky Glabush: Mount Temptation

Past viewing_room

![['Branches in Light'] is a wonderful winter painting, do you want to talk a little bit about it? I always...](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_620,h_620,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/ws-philipmartingallery/usr/images/feature_panels/image/items/27/27d63dd853504775957e2bb2ff82c9bc/sg_2024_branchesinlight_rd_lg.jpg)