The term kinetic generally indicates motion of material bodies and the forces and energies associated with it. Thus to isolate a certain type of film as kinetic and therefore different from other films means we're talking more about forces and energies than about matter. I define aesthetic quite simply as: the manner of experiencing something. Kinaesthetic, therefore, is the manner of experiencing a thing through the forces and energies associated with its motion. This is called kinaesthesia, the experience of sensory perception. One who is keenly aware of kinetic qualities is said to possess a kinaesthetic sense.

The fundamental subject of synaesthetic cinema—forces and energies—cannot be photographed. It's not what we're seeing so much as the process and effect of seeing: that is, the phenomenon of experience itself, which exists only in the viewer. Synaesthetic cinema abandons traditional narrative because events in reality do not move in linear fashion. It abandons common notions of "style" because there is no style in nature. It is concerned less with facts than with metaphysics, and there is no fact that is not also metaphysical. One cannot photograph metaphysical forces. One cannot even “represent" them. One can, however, actually evoke them in the inarticulate conscious of the viewer.

The dynamic interaction of formal proportions in kinaesthetic cinema evokes cognition in the inarticulate conscious, which I call kinetic empathy. In perceiving kinetic activity the mind's eye makes its empathy-drawing, translating the graphics into emotionalpsychological equivalents meaningful to the viewer, albeit meaning of an inarticulate nature. "Articulation" of this experience occurs in the perception of it and is wholly nonverbal. It makes us aware of fundamental realities beneath the surface of normal perception: forces and energies.

Patrick O'Neill: 7362

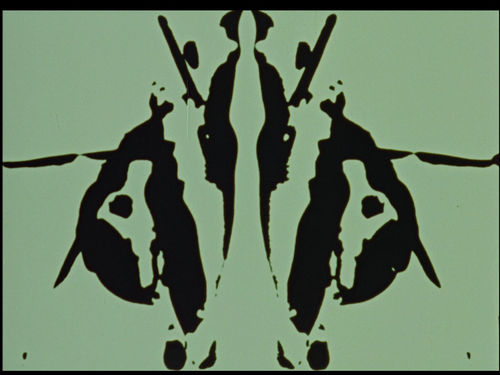

New tools generate new images. In the historical context of image-making, the cinema is a new tool. 7362 is among the few purely cinematic images to evolve from this new seventy-year-old tool. All the visual arts are moving toward the cinema. Artists like Frank Stella or Kenneth Noland have been credited as significant painters within the last decade because they kept the game going. One is impressed that they merely discovered new possibilities for a two dimensional surface on stretchers. But the possibilities are so narrow today that soon there will be nowhere to go but the movies. Pat O'Neill is a sculptor with a formal background in the fine arts. Like Michael Snow, also a sculptor, O'Neill found unique possibilities in the cinema for exploration of certain perceptual concepts he had been applying to sculpture and environmental installations. 7362, made some five years ago, was the first of many experiments with the medium as a "sculptural" device. The term is intended only as a means of emphasizing the film's kinetic qualities. 7362 was named after the high-speed emulsion on which it was filmed, emphasizing the purely cinematic nature of the piece. O'Neill photographed oil pumps with their rhythmic sexual motions. He photographed geometrical graphic designs on rotating drums or vertical panels, simultaneously moving the camera and zooming in and out. This basic vocabulary was transformed at the editing table and in the contact printer, using techniques of high-contrast basrelief, positive/negative bi-pack printing and image "flopping," a Rorschach-like effect in which the same image is superimposed over itself in reverse polarities, producing a mirror-doubled quality.

The film begins in high-contrast black-and-white with two globes bouncing against each other horizontally, set to an electronic score by Joseph Byrd. This repetitive motion is sustained for several seconds, then fades. As though in contrast, the following images are extremely complex in form, scale, texture, and motion. Huge masses of mechanical hardware move ponderously on multiple planes in various directions simultaneously. The forms seem at times to be recognizable, at others to be completely nonobjective. Into this serial, mathematical framework O'Neill introduces the organic fluid lines of the human body. He photographed a nude girl performing simple motions and processed this footage until she became as mechanical as the machinery. At first we aren't certain whether these shapes are human or not, but the nonrhythmic motions and asymmetrical lines soon betray the presence of life within a lifeless universe. Human and machine interact with serial beauty, one form passing into another with delicate precision in a heavenly spectrum of pastel colors.